Augmented Reality in Live Performance

U2 AR

November 2020

Willie Williams

November 2020

Having been exploring mixed reality for years, a frequently raised suggestion is that it would be ‘amazing’ to incorporate this kind of technology into live performance. I’d long felt that, in many ways, VR & AR experiences were the antithesis of what live shows provide; a communal emotional connection experienced in real life and in real time. The question wouldn’t go away, though, and the persistent idea that there must be something interesting to be done with a mixed reality live event eventually led us to investigate further.

The ubiquity of cell phones at concerts has changed the live experience almost beyond recognition. In a remarkable, vibe-crushing triple-whammy, cell phones simultaneously pull focus away from the performer, create a psychological barrier between the members of the audience and minimise the possibility of physical response from individual viewers. However, understanding that this is not something that’s going to change in the immediate future, we began to explore whether there might be an interim experience that could be offered to make some sense of this new, invasive device.

One train of thought began with the throw-away notion that if people were going to be staring at their phone screens during the show, then maybe we could offer up something interesting for them to look at. By 2017, augmented reality had become a staple feature of Snapchat filters and the like. In the art world, Jeff Koons and others had embraced it to place virtual sculptures within urban landscapes, so a general familiarity with the concept had been pretty solidly established.

My observation was that AR used in this way remained a solitary experience. In response, I began to wonder if it might be possible to create an AR experience that could be viewed simultaneously by a large group of people, turning it into a communal experience. This might be something comparable to the way that the solitary activity of listening to music through ear buds becomes a gigantic communal experience in the live concert environment. I felt that this might be of interest to U2, who have spent the past several decades embracing and deconstructing new technology, so began to work on some more specific proposals.

I was aware that to do this would mean clearing some very major hurdles; the technological issues would be far from insignificant but greater still would be the task of coming up with a concept to involve AR in a live show without it becoming painfully clunky. For starters, it would have to be completely effortless and intuitive for the viewer; there’s zero possibility that during a U2 show there could be on-screen instructions, with everybody pausing to get their phone ready and press the red button. I could see that the challenge of creating the technology would likely become secondary to the challenge of invisibly choreographing its usage.

U2 was planning the Experience + Innocence tour for 2018. It was to be an in-the-round show incorporating a very large double-sided LED screen positioned lengthways down the arena, which would prove to be the ideal platform for triggering an AR experience.

During 2017 however, U2 was on the road with a different show, taking their Joshua Tree anniversary tour through stadiums in Europe. One of the logistical upsides of having a client on tour is that you’re pretty much guaranteed to know where they are likely to be at any given moment so, over the course of several weeks, I storyboarded various ideas and was regularly able to engage the band members in the process. U2 had just finished recording the Songs of Experience album which was to form the basis for the following year’s show. The opening track of the album, Love is All We Have Left, is an orchestral/vocal piece that sounded like it might be just the right kind of vehicle for the AR experiment. I focussed all efforts on this piece, with a view to proposing that this might become the opening of the show.

The downside of touring is that, although you know where the band members are, there’s rarely any time to cram in extra-curricular activities and I could see that it was going to be very difficult to carve out time to arrange any kind of shoot with the band members. Sometimes you get lucky though, and on the afternoon of a show day in Amsterdam, I noticed that a motion capture studio had been set up in a room at the stadium, in order to record the band members for some other project that was going on.

Time was extremely short (it was a show day after all) but I did manage to gatecrash the shoot for five minutes, which was enough time to have Bono perform just one single take of lipsyncing to Love is All We Have Left. Happily he nailed the performance in one, so at least from that point we had footage in the can and our goal felt a little more reachable.

The Experience + Innocence show was a sequel of sorts to 2015’s Innocence + Experience, the narrative of which had drawn from the band members’ experiences of growing up in Dublin in the ‘70s. This arc of this narrative was a journey, from their teenage bedrooms out into the world of adulthood. The notion was that the sequel narrative would be about “the journey home” in some form but it was only long into the process of making the album that U2 realised this second ‘journey’ would at least in part have to embrace the journey to the end of life. In the few years preceding the tour, Bono had had a couple of genuine near-death experiences, most famously when he came of his bike at high speed in Central Park and had his fall broken by a large rock. Having survived this, it was unsurprising that the experiences found their way into the new songs, a couple of which refer very directly to a first-hand account of the moment of dying.

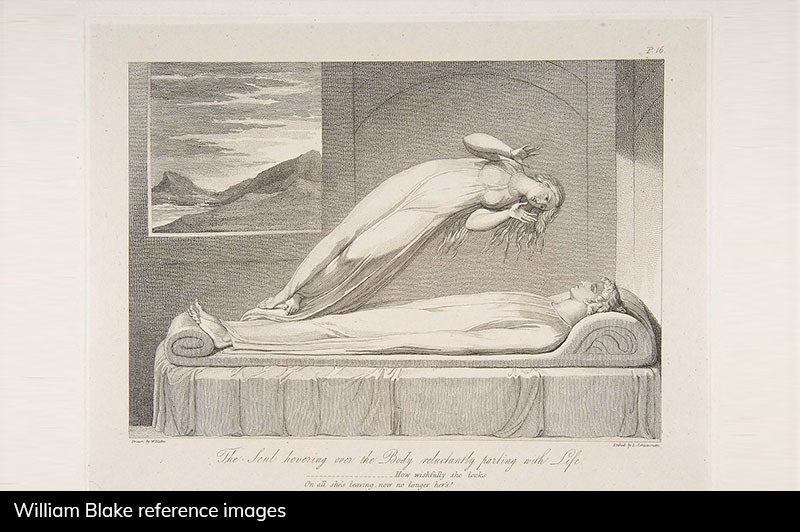

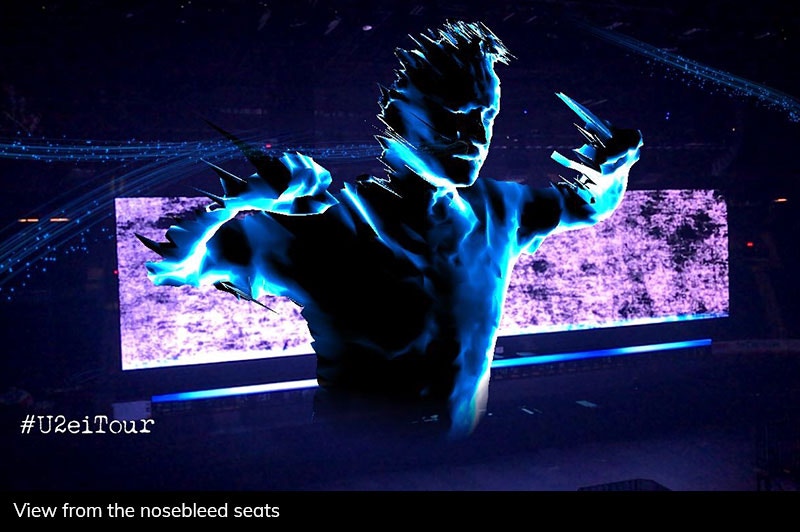

The album titles of course are borrowed from the William Blake cycle of illustrated poems Songs of Innocence and of Experience. We had never made any direct reference to this but, when looking for narrative clues, we began to find some compelling images of the human soul leaving the body. Something about these really resonated and we wondered if this might become the conceptual base for an augmented reality moment in the live show. Could the live performer have an ‘aura’ or a ‘spirit’ of some kind, only visible via mixed reality?

We made a proposal for a show intro, where the LED screen would crack open, the upper half lifting vertically away from the lower, revealing Bono in the interim space between. To stress the connection with the Blake etchings, the initial thought was that Bono would be lying down and would sing Love is All We Have Left as if laid out on a mortuary slab. Above him, would appear his spirit avatar, his ghost, gigantic, filling the arena, dueting on the song lyric. Everyone was very excited about the idea, the enthusiasm only being tempered but the realisation that in order to create this extraordinary moment, the avatar would have to “sing” in lipsync with the live vocal, and stay in sync on a smorgasbord of different phones and devices. Having already taken on the creation of an unprecedented technical feat, we had just turned up the challenge to eleven.

The dual paths of developing the technology and the narrative continued for several months. For Treatment, the core creative team was Damian Hale, David Shepherd and Gareth Blayney who spent several months bringing the vision to life. Meanwhile, for Treatment in L.A., Julia Goldberg headed up the labyrinthine task of ensuring cross-platform compatibility and the minor detail of getting the app into the various app stores in time for the opening of the tour.

The first concrete step was to create the avatar footage and I felt that the best way to do this was essentially to make a standalone video clip for the song, using the 3D motion capture from Amsterdam. Working with Simon Russell, we produced a sequence of the Bono spirit-creature singing, appearing from light out of stardust and briefly becoming flesh before decaying and returning to dust. Aside from being a good technical exercise this really helped us all get to know this avatar character, to build narrative and to solidify the sense of what we were working towards.

More polished versions of the AR app continued to be developed. For the trigger image we decided on a series of black & white abstract chalk textures and it became a great thrill to see the animation come to life wherever the app saw this texture. Prior to arrival at technical rehearsals in New Jersey & Montréal we had achieved pretty consistent functionality but there were still some significant challenges ahead that could only be tackled when we had the complete set up in situ. We had a month left to perfect everything and only now could we begin to address some of the crucial areas, like the audio sync.

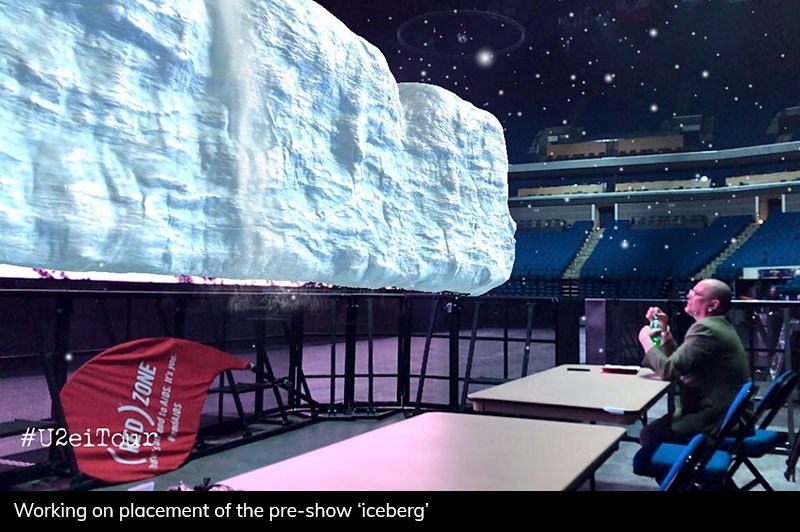

I had made a plan to address educating the audience in the usage of the app and also to create a seamless way into its deployment at the top of the show. On each show day, when doors opened and the public was allowed into the area, they entered to find the LED screen lowered to stage level, bisecting the arena floor. The enigmatic chalk trigger image was on screen which would begin the first AR event. When view through the app, the entire LED screen became a gigantic iceberg filling the central void of the arena. Looking up and around the venue, it was snowing and very occasionally, vague abstract spirit figures would traverse the room.

I was fully aware that only a small percentage of the audience would arrive at the show prepared and ready with the AR app but imagined that word would spread as the tour progressed. What I hadn’t anticipated though was that for every person who did have the app going during the pre-show period, there would be a small crowd gathered around to see what was going on. Consequently, the audience became effectively self-educating, passing the information along in a natural, accumulative way which was absolutely perfect for the low-key approach I’d hoped to take.

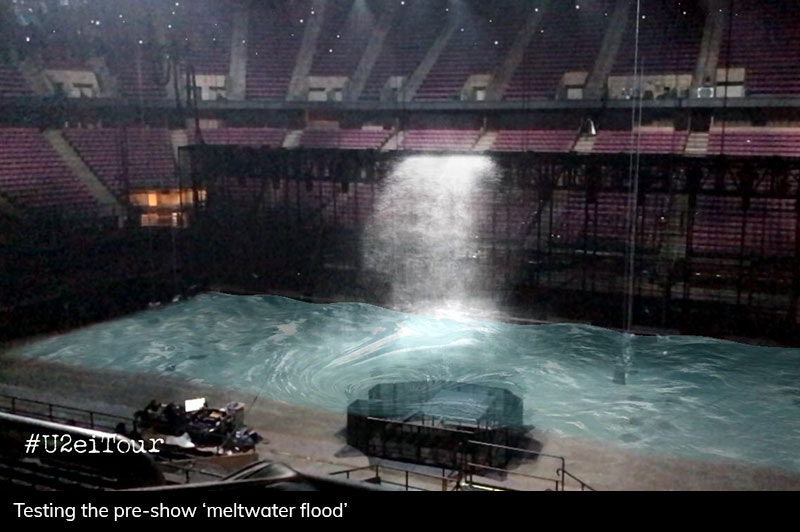

The iceberg sat there happily for about 45 minutes before show time at which point, very gradually, the temperature rose and the iceberg began to melt. A small waterfall appeared in the centre, eventually increasing to a torrent. The snow covering the screen melted away and the water began to fill the floor of the arena. From seats above the ‘water line’ viewers could see the standing audience appear to be immersed and, rather delightfully, viewers on the arena floor had the experience of being under water. Eventually a whirlpool appeared in the water, swirling with objects that would appear again later in video sequences later in the show.

I’d always intended this to be a kind of ‘easter egg’ rather than a grand spectacle, which is very much how it proved to be. The key thing though was that by show time, anyone who was interested in the AR moment fully understood how it worked and what to do. With no intrusive instruction the audience was primed ready to go as the show opened.

During band rehearsals we finessed the performance and got it to completion. In the end, the notion of Bono opening the show lying down proved to be as absurd as it sounds so we opted for the more traditional vertical posture. All the same, it was still an extremely counter-intuitive way to open a show; generally, the energy of anticipation is one of the most powerful weapons in a performers arsenal, so to effectively squander this by opening with a small and fragile moment requires a very great deal of confidence. Effectively, Love is All We Have Left became a kind of prologue, a moment of literal suspension which perhaps suggested that there might be another unseen dimension to everything that followed.

From a director’s perspective it was very satisfying to pull off an entirely new way of opening a show, one borne of eliminating all the tried and trusted methods of approaching an audience. I was also very pleased at how the tone of the AR sequence landed publicly. For all its vast technical complexity, it was always destined to be a fragile, understated moment – designed to thrill through quiet discovery. Had it been overhyped and had audiences arrived anticipating a huge spectacle, the moment would likely have felt a little inconsequential.

The app included the ability to take screen shots, and so record these ethereal moments. Initially we also included a video record function but this proved heroically damaging to battery life. Part of me got a visceral thrill out of the idea of an opening sequence that drained the audience’s phone batteries entirely, thus forcing them to watch the rest of the show in real life. However, humane practicalities, such as being able to get an Uber home after the show, eventually won the day.

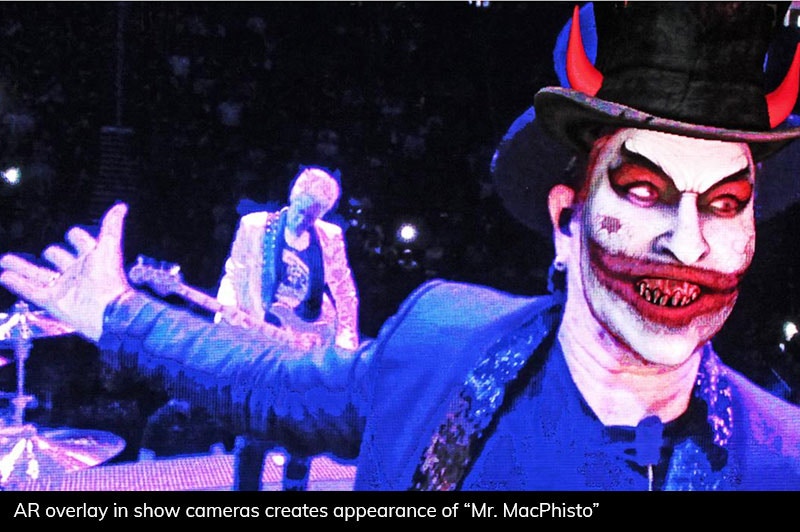

There is a rather nice post-script to the story. Rather unexpectedly, it turned out that this wasn’t the only augmented reality moment in the Experience + Innocence show. During rehearsals we had played with the ‘AR scenery’ approach to adding visual layers to the feeds from the show cameras. This started quite literally with adding SnapChat filters to iMag images which, whilst being a hilarious way to pass an afternoon at rehearsals, clearly wasn’t a strong enough idea in itself.

However, within this show, Bono wanted to incorporate the return of his early-‘90s demonic alter ego ‘Mr MacPhisto’. As part of U2’s Zoo TV show, Bono would undergo a physical costume and makeup change to create the character. In the 21st century though, we were able to transform his onscreen features electronically, and to great effect.

It was a brief moment but extremely impactful and apparently effortless (thanks in no small part to Ric Lipson’s seemingly endless patience in getting the AR facial features just right). Best of all, it didn’t feel like a tech moment, it was entirely about the emotional connection with this disturbing character who had appeared apparently out of nowhere.

Incorporating augmented reality into the show was a monumental task and couldn’t have been achieved without the willingness and support of U2. As we look to the future, we are very fortunate to have collaborators who are open to radically new approaches in our continued quest to reinvent the wheel, time after time.